On a sunny day in August, my wife and I join a few dozen cars' worth of people at a low slung, red-roofed building on the outskirts of Richland, Washington — the B Reactor Branch Headquarters of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, Hanford — for a tour of the atomic reactor that made the plutonium that made the bomb that destroyed Nagasaki.

We check in, watch a short safety video, and board the bus for the forty-five-minute ride across the Hanford Reservation to the reactor. As we cross the treeless shrub steppe of the Columbia plateau, our tour guide, a retired Navy nuclear engineer, points out some of the flora and geology of this former glacial lakebed.

In May of 1942, a few weeks before his 20th birthday, my father volunteered for the British Navy. He joined the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious, which was bound for the Indian Ocean to support a preemptive invasion of Vichy France controlled Madagascar to forestall a potential Japanese occupation. With a diploma in electrical engineering, his job was to look after the radio, and later radar, systems in the ship's ever-changing roster of aircraft.

A month later, the Manhattan Project, the United States' World War II project to build an atomic bomb, was initiated, in part at the urging of British scientists and out of concern that Germany might be working on the same thing.

By December there were concerns that the main project site at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, was too close to a major population center in case of an accident, and that a more remote site was needed. The Hanford site in south central Washington was chosen. On the Columbia Plateau in a bend on the Columbia River, it was remote from major population centers, and had abundant water. Power lines connecting the newly-built Grand Coulee Dam upstream to the Bonneville Dam downstream passed right across the site.

Our tour guide points out some of the buildings on the Hanford site, including the vast plutonium chemical separation plant, nicknamed the Queen Mary. The tour bus rounds a bluff, and Reactor B, along with the entombed reactors D and F, comes into view. It's smaller than I had imagined.

In 1943, HMS Illustrious, with my father aboard, was assigned to European waters, first the Norwegian Sea and later the Mediterranean in support of the landings at Salerno. Between these assignments, she provided air cover for the real RMS Queen Mary as she conveyed Prime Minister Winston Churchill to the Quebec Conference.

At the conference, President Roosevelt and Churchill signed the Quebec Agreement, merging the British Tube Alloys bomb project into the Manhattan Project. Development of the Hanford site commenced that year. The towns of Hanford and White Bluffs were emptied, and local Native American tribes denied access to their traditional fishing and gathering places along the Hanford reach. Uranium oxide started shipping from Shinkolobwe in the then Belgian Congo.

The tour bus stops at the security gate. After a brief conversation with the driver and guard, the barrier is lifted, we drive into the complex and approach the rather unassuming reactor building. We disembark, leaving any snacks behind on the bus, and walk past a row of bright blue plastic porta potties into the entry hall.

HMS Illustrious headed back to the Indian Ocean in 1944 to join USS Saratoga for combined operations against the Japanese facilities in the Dutch East Indies and the Andaman Islands and remained for further operations in the Indian Ocean.

Hanford Reactor B went critical and started producing plutonium. The first batches were shipped to Los Alamos.

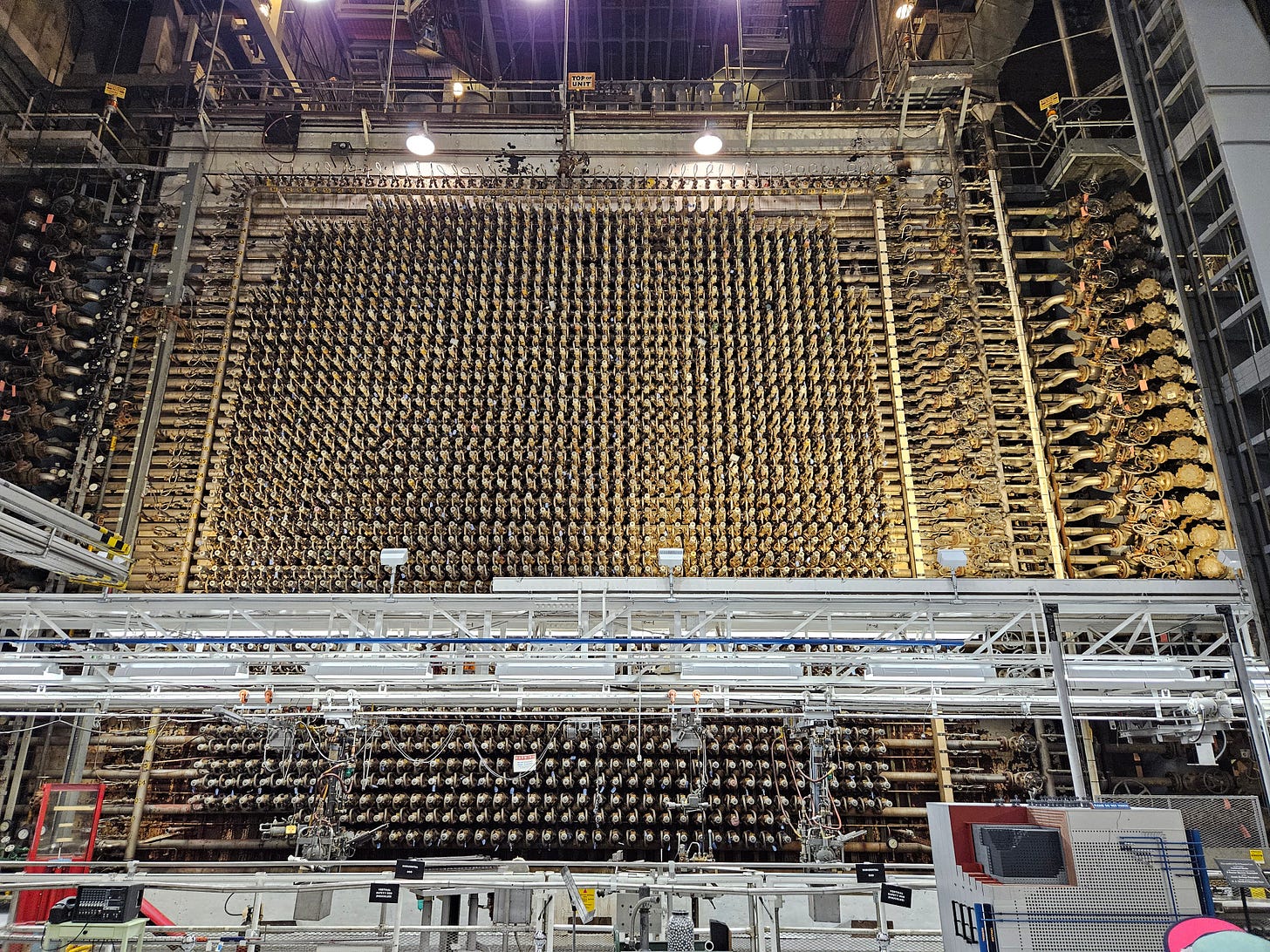

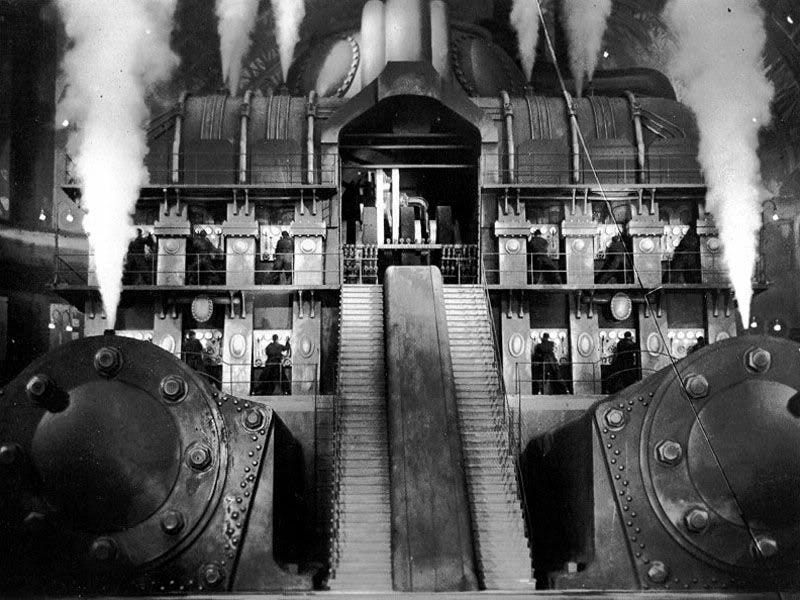

From the lobby, we enter the charging area, a large room where we're looking at the front face of the reactor. It's as if Fritz Lang had built Metropolis's Machine Room with graphite Lego blocks.

Here slugs of uranium fuel in aluminum cans are loaded into the two thousand and four tubes in the reactor face. Water passing through the tubes at seventy-five thousand gallons per minute keeps the slugs cool. We see the back face of the reactor where irradiated slugs are pushed out and drop into a pool of water. Two thousand and four aluminum alimentary canals eating uranium and shitting plutonium. Workers fish out the slugs and transfer them to a tank of water where they're taken by train to the chemical separation plant where a tiny bit of plutonium is recovered from each slug. There are two empty flat cars between the locomotive and the tank.

Illustrious was transferred to the BFF - the British Pacific Fleet - based in Sydney, Australia in 1945. Her final action of the war was to neutralize airfields in the Sakishima Islands in support of the American invasion of Okinawa. Suffering from damage accumulated over several years of heavy action, she returned to the UK, arriving on June 27, 1945, shortly after my father's 23rd birthday. He had spent most of the past three years at sea.

Less than a month later, plutonium from Hanford was the fuel in the first nuclear bomb, detonated at the Trinity site in New Mexico on 16th July 1945.

The 'Little Boy' bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6th, and the 'Fat Man' bomb, also made with plutonium from Hanford, was dropped on Nagasaki on August 9th. Under the terms of the Quebec Agreement, British permission was required and was given. Japan surrendered.

The war over, my father was demobilized, exchanging his uniform for a "demob suit", and went to work at the glassworks where his father was works manager. A taste for Player's Navy Cut cigarettes and tea without milk were the only outward signs of his service.

We see Enrico Fermi's office. Fermi, one of the scientists on the Manhattan Project, had supervised the startup of the reactor.

The McMahon Act of 1946 in the US ended nuclear cooperation with Britain. The "special relationship" was not so special after all, and Britain felt she would have to develop her own bomb or risk losing her "Great Power" status. And so, the following year, work commenced on a close copy of Hanford Reactor B at the Windscale site in Cumberland, north west England. The site lacked access to a large river, so it was decided the reactor would be air- rather than water-cooled.

At the glassworks, my father met my mother. They married in 1948 and moved in with her mother and brother.

The tour takes us past the control rods and safety rods that could quickly shut down the reactor in case of a problem.

In 1949, the Soviet Union detonated a 'Fat Man' style plutonium bomb. The Hanford B Reactor was converted to produce tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, needed to make an H-bomb. This involved replacing some of the uranium fuel rods with a lithium-magnesium mixture.

My father saw an advertisement for a job offering better pay, lots of overtime, and, most importantly, guaranteed housing. Tired of living with his mother-in-law, he packed my mother and their belongings into the BSA three-wheeler and headed off to a new life at Windscale working as an electrician on the reactor's measuring and control equipment. The housing turned out to be a council house in Whitehaven, a nearby coal mining town. It was the kind of town where you'd bring your laundry in off the line at night or risk having it stolen. But it was a house.

In the Reactor B control room, we see the kind of equipment my father would work on at Windscale. Temperature, pressure, radiation, and other sensors are connected by miles of wires to dials, meters, lights, and chart plotters.

Switches and buttons are connected back to pumps, motors, and control rods. The reactor can be run by three people, but many more are behind the scenes keeping those controls working.

Windscale Pile No.1 went critical in 1950 and No.2 in June 1951. Three months later, I was born at Whitehaven hospital. I had my own ration card. In the 50s equivalent of today's active shooter drills, the US Federal Civil Defense Administration made the film Duck and Cover, to teach schoolchildren what to do in the event of a nuclear explosion.

Five days after my first birthday, Britain's first nuclear bomb was successfully detonated in the Operation Hurricane test in the Monte Bello Islands in Western Australia. I guess that makes me a baby boomer. My mother would take me to St Bees Beach, a few miles up the coast from Windscale. Later that year, my parents relocated to near Portsmouth in the south of England, where my father had been stationed for a while during the war, and where my brother was born the following year.

The tour takes us to a health and safety exhibit where we see the protective equipment worn by the workers, and similar to that my father would have worn.

In 1954, the US successfully tested an H-bomb at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. French designer Louis Réard designed a two-piece swimsuit and named it 'bikini' after the atoll.

Britain, of course, must also have a H-bomb, with the possibility of a test ban treaty between the US and the USSR only adding to the urgency. Within a year, the piles at Windscale, already at the end of their design lives, were retrofitted to produce tritium. Retrofitting an air-cooled reactor with highly flammable lithium-magnesium was a recipe for disaster, and it struck in the form of the Windscale fire of 1957, when a fuel canister leaked and caught fire. The radioactive plume stretched into Europe. Radioactive iodine settled on fields where cows were grazing, got into their milk and from there into the thyroid glands of those who drank it. Hundreds of people eventually died of thyroid cancer. The fire was the main topic in the news for weeks. I learned that my father had worked there and my young scientist brain absorbed all he could tell me about radioactivity and chemistry. The Windscale piles were shut down, and the site rebranded as Sellafield.

The following year, Britain's Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament held its first meeting and began the annual marches from London to Britain's Atomic Weapons Establishment near Aldermaston. The marches were featured on the news every year, accompanied by disgruntled mutterings from my father and a growing curiosity from me. The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 and the release of Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb in 1964 changed American public perception of nuclear deterrence. Hanford Reactor B closed in 1968.

On the tour, I recall that Hanford is actually not my first reactor.

I headed off to the University of Manchester to study chemistry in 1969. Many of the scientists working on the Manhattan Project were also noted for their contributions to quantum mechanics and physical chemistry, and the list of names in class was like the cast of Oppenheimer; Heisenberg, Einstein, and Fermi, while one of my professors had studied under Niels Bohr.

In my senior year nuclear chemistry class, we visited a research reactor at Risley near Manchester, which had been the headquarters of Britain's bomb project. In the class, I learned that the sand at St Bees Beach, where my mother walked me as a toddler, was so radioactive it was illegal to send it in the post. I decided to make radioactive waste the subject of my class project. What I learned in the library cemented my senior year emergence as an environmentalist.

I notice a couple on the tour who might be Japanese American. It seems impolite to ask, but it triggers another memory.

After moving to the US, in 1985, I visited Japan on a work trip. Late one evening, a coworker took me to a Karaoke bar. The owner, who went by Mama-San, had two daughters. One wanted to sing for me. She sang two songs, one in English, her first ever, and the other a beautiful, haunting song in Japanese. I asked the gentleman sitting next to me what it was about.

"It's about the old Nagasaki. Mama-San was a child there when the bomb came." I felt no judgement, just an invitation to share in their grief and to accept their forgiveness.

Back in the the US, I took some visitors to the UN building where there was a Hiroshima exhibit. I looked at it for a very long time.

Chernobyl pushed Windscale off the top spot in the nuclear disaster league tables in 1986, to be joined by Fukushima in 2011. Like Windscale and Three Mile Island before them, the cause of each disaster was a reactor core fire and loss of coolant.

The last stop on the tour is the valve pit, containing the pumps, pipes, and valves bringing the cooling water from and returning it to the Columbia River. Inspection hatch covers have been removed, and judging by the rust on them, have been that way for some time.

In 1987, our sales rep in California sent me a piece of printed circuit board for testing. It was small, about the size of a thumb nail, and came from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. I asked what it was.

"Oh, it's part of the trigger for an H-bomb."

"What? I just have a green card, I'm not even a citizen, are you sure I can even see this?"

It was the height of Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative, known as "Star Wars", the objective of which seemed to be to outspend the Soviet Union into submission. "Leaks" were part of the program of sabre-rattling, or "willy-waving", as the Brits call it. That year, Reagan and Gorbachev signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which reduced the size of US and Soviet nuclear weapons stockpiles. Part of the treaty was an agreement to stop producing plutonium, as the world already had more than enough.

As it's impossible to run a reactor like Hanford B without cooling water, removing the valve pit hatch covers provides verification to Russian inspectors that the reactor has not been used.

As the bus drives us back to Richland, our guide shares a few words about the cleanup happening around the site.

Fifty-five million gallons of radioactive waste from the fuel processing plant and elsewhere is stored on the Hanford site. Radioactive contamination is leaking into the groundwater and the Columbia river. Ten thousand workers are involved in a cleanup which is due to last until at least 2070, a full century after the reactors were shut down, with costs that may reach a trillion dollars.

Sellafield, a 'bottomless pit of hell, money,and despair' is Europe's most toxic nuclear site, with cleanup costs estimated at over £200 billion. According to the Cumbria Wildlife Trust, the last radioactive particle has been picked up from St Bees Beach, over seventy years after my mother walked me there.

Entwined with the story of the bomb is a story of human suffering with both intended and unintended victims.

The bomb would not have been possible without the work of Jewish and other refugees from their mistreatment in Nazi Germany and neighboring countries. It's possible that, but for Hitler's antisemitism, Germany might have had the bomb first.

Uranium oxide from the Shinkolobwe mine was produced under conditions approaching slavery. Aside from the health consequences of breathing uranium oxide dust, the country has been has been a geopolitical football ever since with democracies undermined and dictators supported by the US and others.

Black and white Americans worked on the Hanford site, but in segregated crews living in segregated housing. That for the Black Americans was of a lower standard.

Native American tribes were displaced from their traditional fishing, hunting, and gathering places along the Hanford Reach, the last free-flowing stretch of the Columbia river. At the Hanford Journey, Yakama Nation youth, elders and scientists share stories about a land that is a part of them.

From US soldiers deliberately exposed to atomic bomb blasts, to "downwinders" who lived near Hanford and the test sites, to those deliberately injected with plutonium, the US government carried out radiation experiments on thousands of people, none of whom could provide informed consent.

And, of course, hundreds of thousands died during and subsequent to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

If we know better, can we do better?

Thanks, as always, for reading or listening.

John I had so many goosebumps when I was reading through this piece. I am bookmarking this essay for re-read simply because it is so information dense and touches on rich history and how seemingly individual and disjointed decisions are always connected to the larger picture. I am so amused by your connection to the whole WWII era - so directly even.

And thank you for acknowledging all the destruction and suffering this weapon has ensued, this story would have been incomplete without it. Your closing paragraphs and mama-san’s story made me cry, it reminded me of Isao Takahat’s heart wrenching studio ghibli movie- Grave of Fireflies 💔

Wow, this was gripping, John—weaving your dad’s and the larger social story into your tour visit. Truly a depraved atomic bomb escalation, with a price that people are still paying, and will continue to pay. I remember Duck and Cover drills, and being terrified of the Cold War right through the ‘80s. It was something that you just had to not think about if you had no power to do anything about it. Sometimes I wonder how much of the current culture of denial—of climate change, of disabling viruses—was trained into us during those decades. It is not insignificant.