Syzygy

A king tide update

It’s been a difficult month for weather here in the Pacific Northwest. Although the king tide and atmospheric river combo that we referred to a couple of weeks ago passed without causing coastal flooding here on Whidbey Island, our mainland neighbors suffered catastrophic flooding from the accompanying rain, while another storm shortly afterwards knocked out power to most of the island for several days. Here’s a nerdier post than usual on why winter is the season for coastal flooding.

There’s no voiceover this week, as you need to look at the pictures!

NOAA

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services (CO-OPS) maintains a network of water level stations around the coast and great lakes. The nearest station to me is in Port Townsend, Washington. In addition to water levels, the station’s website maintains a database of historical meteorological information, making it just the resource I needed for this post, as coastal flooding is driven by both astronomical and meteorological factors, with climate change impacts, in particular sea level rise, of increasing importance.

NOAA CO-OPS is a great example of the kind of critical federal government service that is being sacrificed by the current regime, for example by the threatened dismantling of NCAR, the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, CO. I visited this facility in 2023. I urge you to visit while you can and to push for its survival.

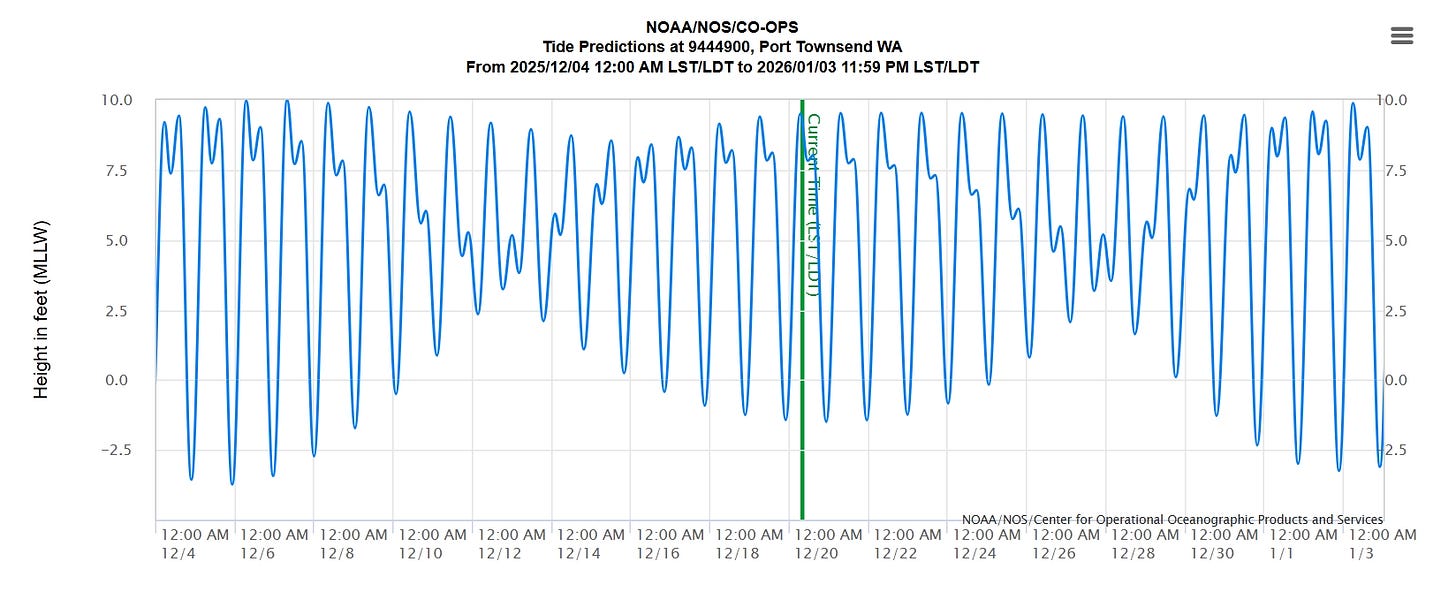

Astronomical

The gravitational pull of the moon as it orbits the earth, and to a lesser extent of the sun as the earth orbits around it, cause our daily tides. At full and new moon, the three bodies are roughly in alignment, called a syzygy, and tides are a little higher than at other times of the month.

The moon’s orbit is elliptical so its distance from the earth varies. The closest point is called the perigee, and, while independent of the moon’s phase, overlaps the full moon several times a year.

At these times, the moon appears larger and is sometimes called a supermoon. Tides at these times are also more extreme and are called king tides.

Earth’s distance from the sun also varies, but here the variation is annual, with the closest point, called the perihelion, reached in early January and raising winter king tides a little higher still than those at other times of the year.

Meteorological

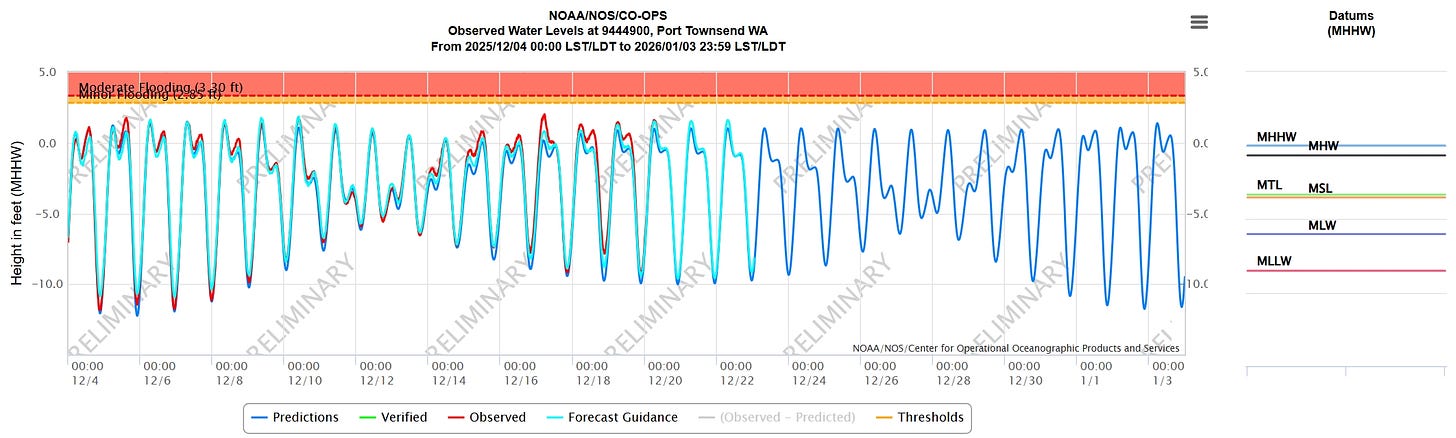

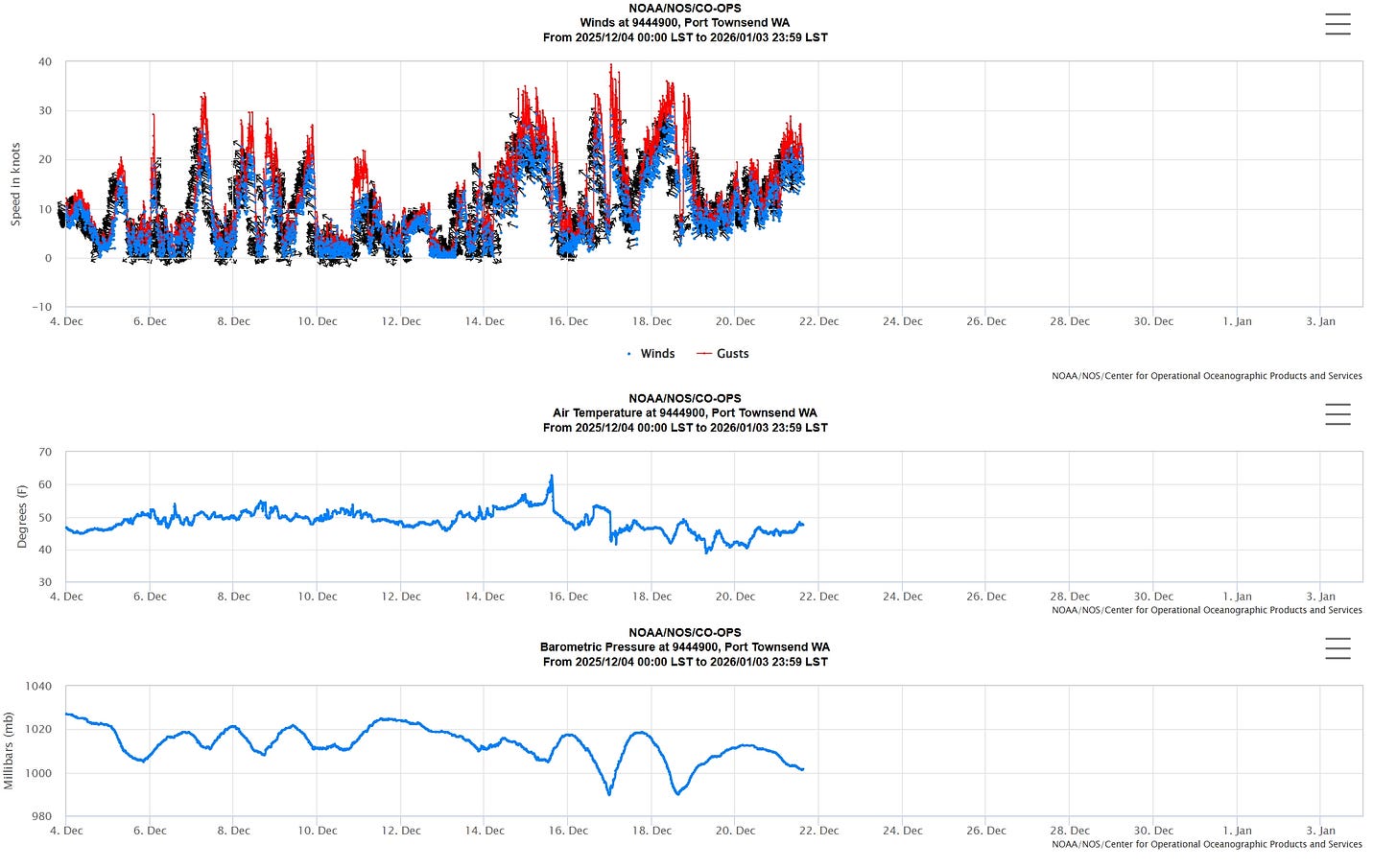

In addition to the astronomical impacts on water levels, meteorological factors can cause a sea level anomaly, or variation from the predicted level, with a two-foot anomaly sufficient to turn a high tide into a catastrophic coastal flooding event. The main meteorological factors are low atmospheric pressure, wind, precipitation, and waves. Unfortunately, these are not independent phenomena. They tend to occur together and more often in winter when king tides are highest,

The data history at NOAA’s Port Townsend station allows me to go back and look at tides and weather during recent coastal flooding events and near misses.

December 2025

Let’s look at the near misses this month, first the king tide and atmospheric river combo on December 5, 6, and 7 that we discussed a couple of weeks ago. This event passed the island by, as the atmospheric pressure didn’t drop below 1000 mb, and we were rain and wind shadowed by the Olympic Peninsula. Our neighbors on the mainland and in British Columbia, however, suffered catastrophic flooding from the accompanying rain falling in the mountains and swelling the rivers.

Another severe storm hit us in the early hours of December 17. Weather data shows the pressure drop to about 990 mb and the strong winds that followed it.

These were westerlies through the strait of Juan de Fuca which pushed water into Puget Sound and combined with the low pressure to cause a tidal anomaly of almost two feet, fortunately on top of a rather ordinary high tide, and once again, we were spared coastal flooding.

The winds, gusting to 71 mph on the west side of the island, took out power to almost the whole island for several days. If all that had happened ten days earlier, during the king tide, we would have had serious coastal flooding.

We were lucky.

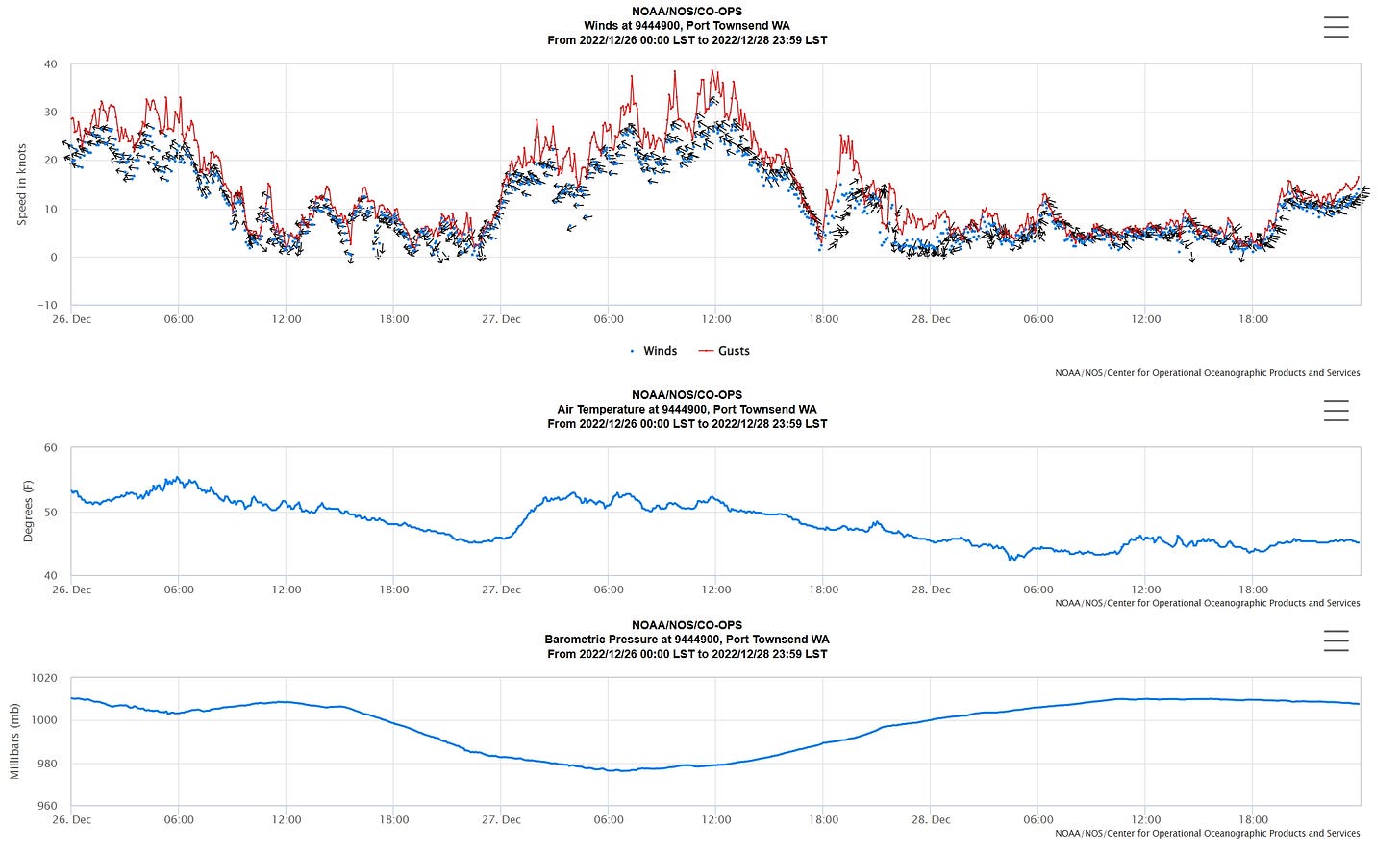

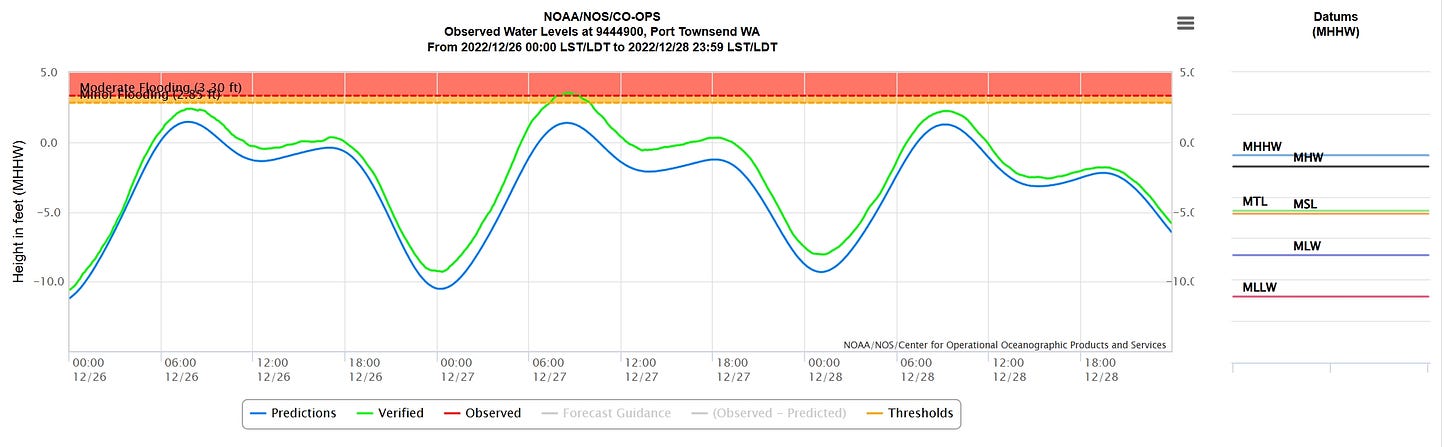

December 27, 2022

Three years ago, we were not so lucky. This was the storm that inspired the first in this series of posts on sea level rise.

An atmospheric pressure of 975 mb and strong winds caused a two-foot tidal anomaly, but this time on top of a king tide, setting the record for the largest anomaly above median high-high water (MHHW), the benchmark for flood stages.

The result was widespread flooding around the island.

Snow followed by rain in the preceding weeks had saturated the ground, which may have contributed to the phenomenon of emergent groundwater, where the rising sea level also lifts the adjacent nearshore groundwater and causes fresh water to bubble up through the ground.

At least the power stayed on for this storm.

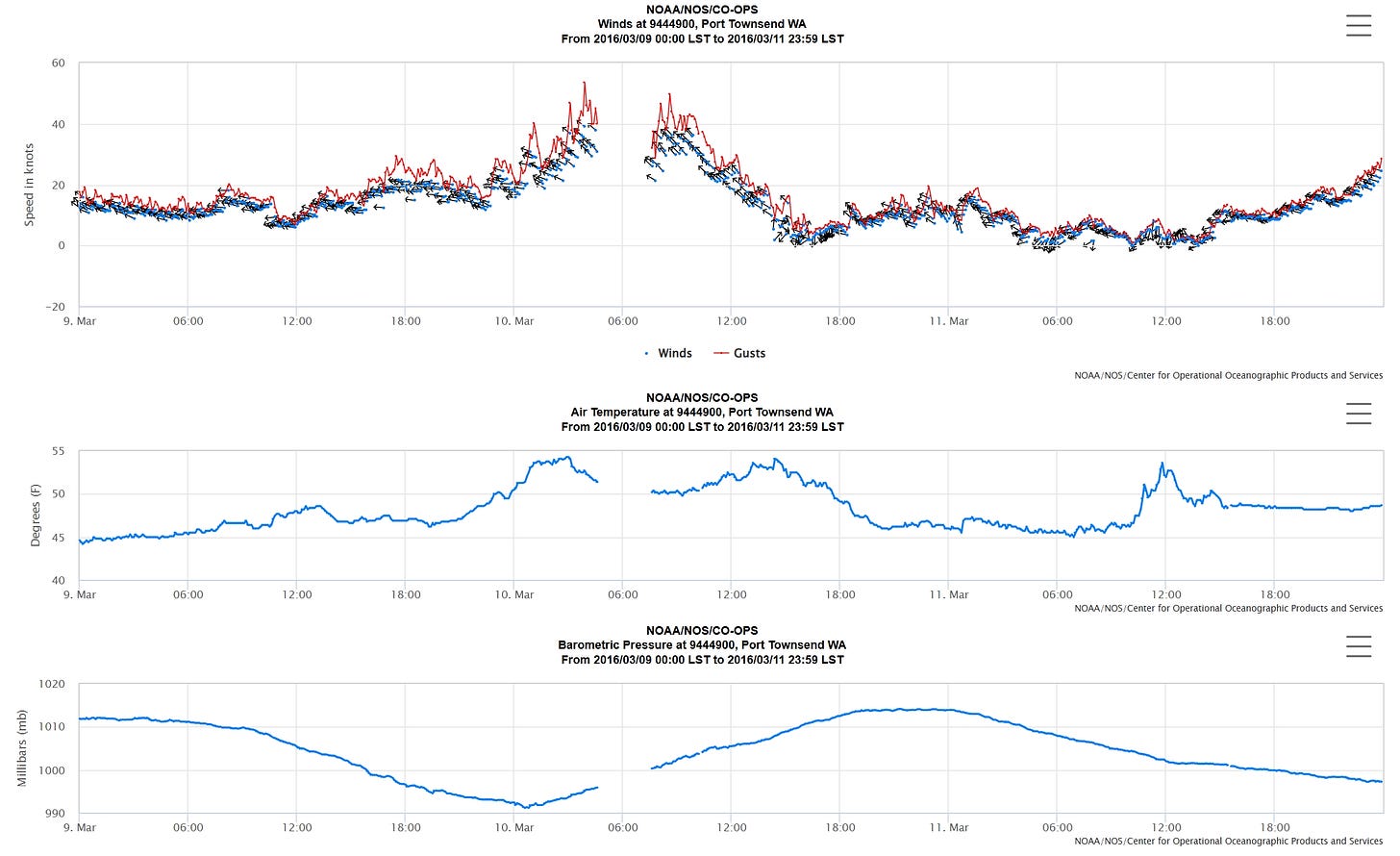

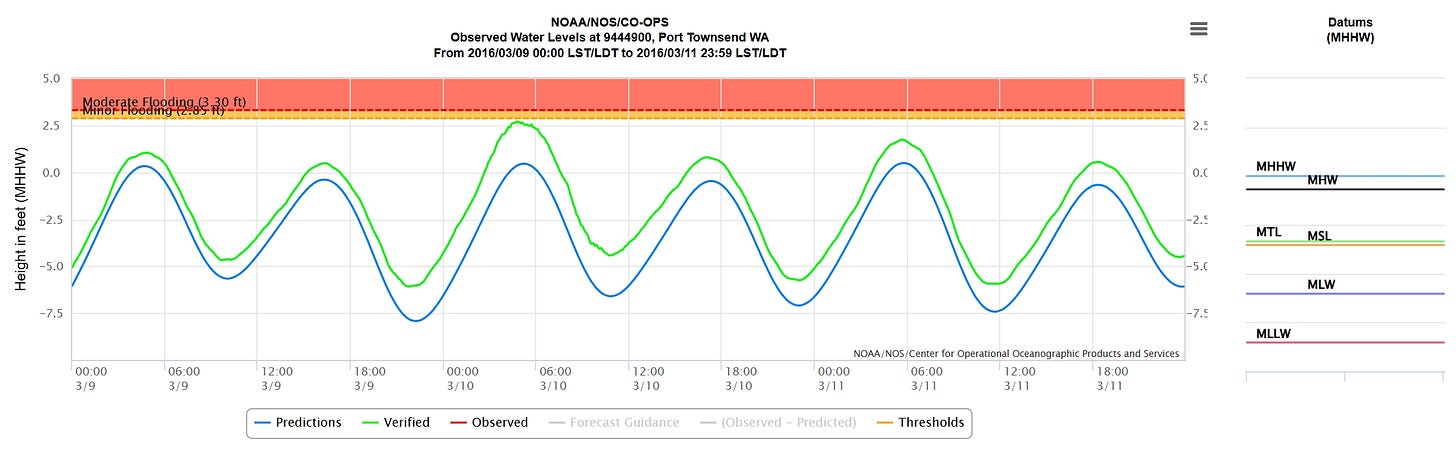

March 2016

In an earlier flooding event, it did not.

March 10, 2016, was my first real encounter with coastal flooding since moving to the island. I spent the day helping a friend pump out his first floor with a rented gas-powered pump, until emergent groundwater left nowhere for the water to go.

The power outage affected Port Townsend too, as can be seen by the gap in the record as the winds picked up.

The wind and low pressure caused a 2 ft 3 in tidal anomaly, the largest in recent years, but on top of a rather ordinary high tide. As the water level above MHHW was not that high, this storm didn’t make the cut as a flooding event in the records.

Flooding was nevertheless severe in exposed places on the island. The extra factor in this storm was the wind direction. Winds from the south-east can have a fetch as long as 40 miles as they reach the island and combined with the shallowness of our local Useless Bay can produce damaging breaking waves on our south facing local beach. The resulting wave overtopping caused severe local coastal flooding, much worse that the water level at Port Townsend would suggest, with the power outage adding to the misery.

Sea level rise

Conservative estimates are for a foot of sea level rise in Puget Sound by 2050. Adding a foot to the current sea levels would have given us several more storms of the severity of December 2022’s. Sea walls can help against wave overtopping and erosion but are of little use against sea level rise as water can find its way around the back of the defenses or simply come up through the ground.

The State Of Our Shorelines

Whidbey Environmental Action Network, WEAN, recently published a Storymap, The State Of Our Shorelines, about land use and climate impacts on the shorelines of Whidbey and Camano Islands in Washington State, and where we go from here. I was a contributor and reviewer for this project.

In January, I’ll be joining WEAN’s executive director, the county’s natural resources manager, and a county commissioner on a panel at a leadership workshop to discuss these shoreline issues. We’ll each have the opportunity to give a framing comment to jump start the conversation. Here’s my topic:

What hard questions do we need to be asking ourselves and what hard conversations do community leaders and citizens need to be engaging with to realistically achieve climate-resilient shoreline management in Island County, especially considering sea level rise projections of about a foot by 2050 and increasing storm intensity and storm surges that are already impacting our beaches and shoreline communities?

A great question. I’ll be posting in January on how it goes.

Thank you, as always, for reading. To make sure you don’t miss the next, please consider becoming a free of paid subscriber.

Syzygy might be my favorite word. I am glad your power is back, I know that can be very disconcerting. I am glad you have a level head about the reality of all this, and your island community is lucky to have you articulating the questions to help figure out the future.